Genesis

Life in the outdoors and all my relations, human and other. Welcome to Totemtik.

Whoever even once in his life has caught a perch or seen thrushes migrate in the autumn, when on clear, cool days they sweep in flocks over the village, will never really be a townsman and to the day of his death will have a longing for the open. – Anton Chekhov, “Gooseberries”

It was one of those late May afternoons in the North Georgia mountains when the mountain laurel and rhododendron were in full bloom, the air lacked the stifling humidity that would be coming in a few weeks, and the state’s best trout water was still too cold to wet wade. I had brought my son to fish a stretch behind an old friend’s stunning property and mountain cabin.

A few weeks after retiring last February I tracked down an old friend. As boys, we had two mad passions: slalom (water) skiing and fly fishing. Richard kept doing both his entire life, in fact still competing at 62 as one of the state’s top senior amateur slalom skiers. At 21, I got distracted by birds, shotguns, and dogs. (The story of how that happened is a future post.)

Richard’s father was not much of an angler. But mine was. At 11 or 12 when we decided that we were so accomplished with spinning and bait casting equipment that we would graduate to fly fishing, dad would humor us. Packing a weekend’s worth of gear in mom’s station wagon, he would plant us on a creek in the Blue Ridge mountains, where we camped, he cooked and watched us struggle to not catch fish in places we easily caught them with worms or corn.

Dad did not take up fly fishing until some years later. But having been a camp counselor as a teenager in those mountains, he damn sure knew how to catch trout in those creeks. Many days, but for that ability - or a can of Dinty Moore beef stew and a loaf of what dad called “skinny white bread” - we 12-year-old fly fishing “experts” would have gone to bed in our tent hungry.

We lived in different school districts, went to different high schools, and as a result had different groups of friends. I went to college out of state and but for a brief stint home afterward lived in Florida for the better part of eighteen years.

Through all that we simply lost touch. When I finally moved home and started a family with my wife in 2000, but for a brief interaction a few years later, with work, family and a different group of friends, Richard and I never really reconnected. Shame on me.

Thanks to another friend who had moved to Wyoming from Pennsylvania a few years earlier, after nearly forty years, I came back to fly fishing in 2021 (another story which will appear in these pages). Not long after retiring and enjoying weekly blissful afternoons chasing trout in the North Georgia mountains, I started thinking about Richard and our fly-fishing days as kids. I knew he had sold the family business and retired several years earlier and had a cabin not far from Mom and Dad’s old place. In fact, while I was living in Florida, Richard and Dad fished together on occasion.

I don’t even remember how I tracked him down last spring. After a couple of calls and texts, we agreed to meet at the local fly shop in the small, quaint town of Blue Ridge, not far from the small space Dad had once leased for the little commercial real estate brokerage that was more an outlet to stay busy and involved in the local community than a business. Before we headed out of town, Richard wanted to introduce me to his friend who owned the business next door to the fly shop.

Bill Oyster is one of the world’s premier builders of custom bamboo fly rods. Richard and Bill had become friends several years earlier. We had time for a brief introduction while Bill was in the midst of teaching a full class of students. He teaches a fly rod building class every other week for about eleven months out of the year. People come from all over the world to spend a week making their own custom bamboo masterpieces, and his classes are booked more than a year in advance.

Richard has built two rods in Bill’s shop (so far..), a 4 weight trout rod and a 9 weight bonefish rod. This day he’d brought the 4 weight rod, an ideal tool given where we were headed. That work of art is pictured below.

I loaded my gear in Richard’s SUV, and we headed to fish a small, heavily forested mountain stream. These were the kind that tortured us as unaccomplished twelve-year-olds almost five decades earlier. We caught more trees than trout.

We discussed our post college lives as Richard navigated the winding roads through the verdant Toccoa river valley; careers, wives, kids, brothers, and sisters well remembered. Our father’s sad endings, as well as my own mother’s. Fortunately, Richard’s mom is still alive and doing amazing despite advanced age.

After a fifteen-minute ride reminiscing we arrived at a stretch of a designated artificial-only stream Richard had passed many times but never fished, a place we chose only because I had caught a nice rainbow there three weeks earlier. We continued making up for lost time as we rigged up, and walked a path tight with rhododendron and mountain laurel in full bloom along the east bank of the small creek. We crossed the creek far enough below the stretch we intended to work to avoid spooking fish.

Richard walked upstream along the other bank twenty yards or so, and we both quietly eased into the creek and began fishing upstream into the fall and small pool where I had surprised a nice rainbow the month prior.

Since the last time Richard and I had fished together in the mountains as kids, the highly technical fly-fishing required by the rhododendron and oaks pinching in from both sides of the creek had morphed from an endless source of childhood frustration to something else: a welcoming, verdant, intimate theater, requiring stealth, technique and positioning. For an hour or so, we were twelve-year-olds again, only now with some damn ability. As I watched Richard work upstream with a nifty little 7 ½ foot 4 weight bamboo rod, it was evident he had acquired a lot more than that.

Richard let his line ride downstream inches away from the stream’s tangle-covered bank, with the tip of the bamboo masterpiece held high just beneath the oak branches growing out over the creek. With great skill he laid out roll casts - the only sort possible fly-fishing in such a tight mountain creek - landing the caddis fake on the crystal clear water as softly as a butterfly with sore feet, always in the ideal spots a few feet above where the water’s flow would cause a feeding trout to hold, and hopefully draw its attention to the caddis riding on the surface or the pheasant tail nymph suspended in the water column beneath it.

Holding the rod at shoulder height and stretching his arm out almost parallel to the running water, he mended the line like an expert, keeping it above the dropper rig so that the varying rates of the water’s flow between his position and where the fly needed to drift motionless would not bow the line and drag the flies sideways unnaturally, giving away the game to any trout looking upward into the current for a meal.

It was three weeks after I’d caught one nice rainbow in the spot, and the water was now warmer in this lower stretch of the creek. We were able to stalk and spot a few fish but could not get them to eat any of the patterns we threw at them.

Yet unlike when we were kids, there was no frustration in getting skunked. We watched each other throw perfect casts into perfect spots and work perfect drifts but simply catch no fish. We told more stories, talked and laughed on the casual stroll down the trail through the forest back to Richard’s truck, and on the short ride along the two-lane road back into town.

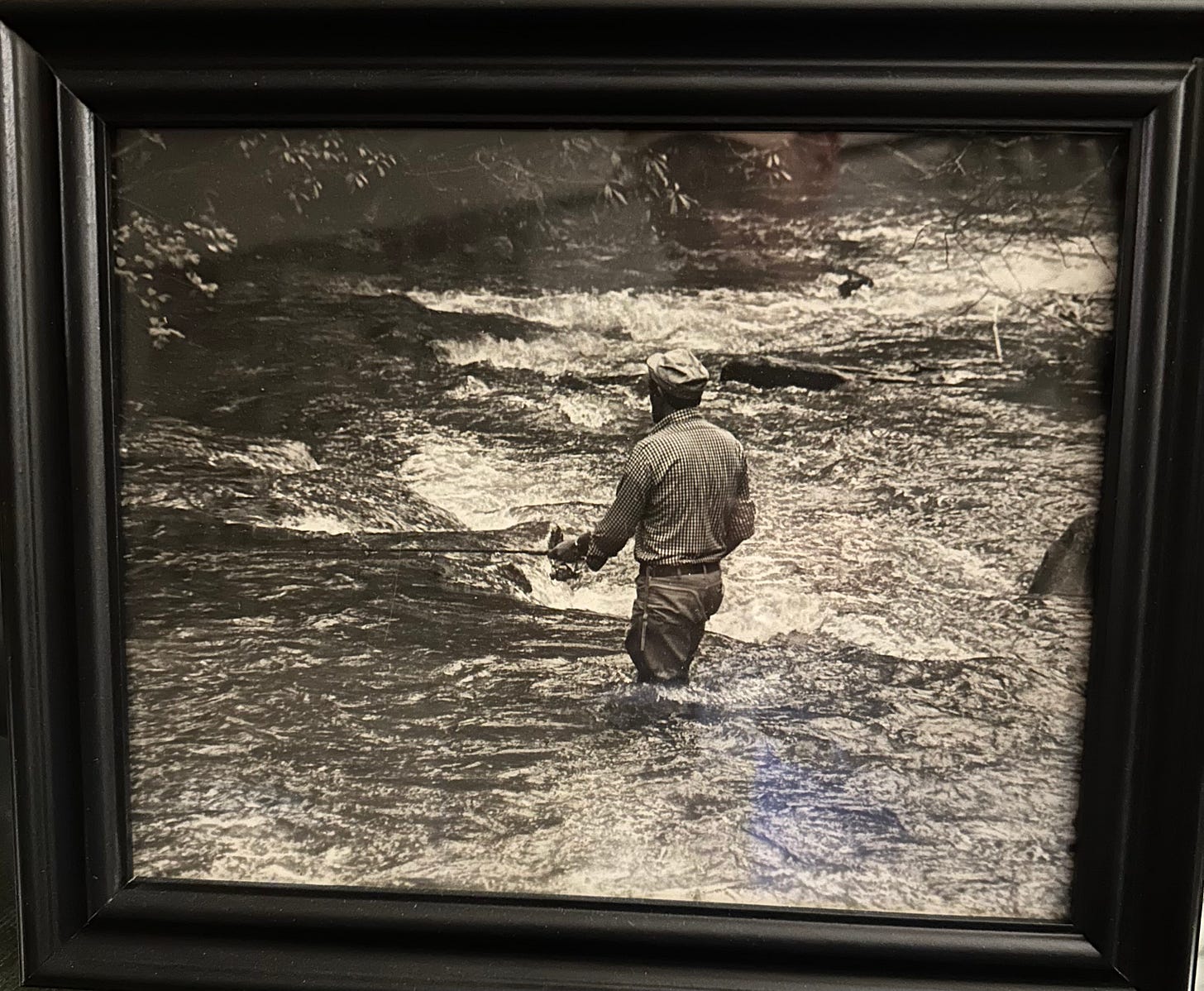

Once there, as I finished throwing the last of my gear into my truck, Richard reached into the back seat of his SUV. As we were about to shake hands and say goodbye, Richard handed me something. “I had two copies of this. I took this of your dad all those years ago on of one our camping trips. I’ve had one hanging in our cabin up here for years.”

Dad had gotten the photography bug and built a dark room in our basement when I was about 10. I had forgotten that Richard and I also decided at about 13 we would not only become world-class fly-fishing experts, but famous photographers also. (My own half-hearted attempts will grace these pages.)

The framed black and white picture of my father, in a mountain creek circa 1977, taken by twelve or thirteen-year-old Richard nearly fifty years earlier caused an instant lump in my throat. There was Dad, in his hip boots with a little ultralight spinning rod. He would have been around 40 at the time.

I smiled, speechless for a moment, trying to make the tears welling up in my eyes go away. In retrospect, whatever gratitude I fumbled to express fell far short of how profoundly moved I was by the incredibly thoughtful gift. That framed picture now faces me, and will, as I write each post for this new Substack.

Fifty years had passed, as had both of our fathers. But with that thoughtful gesture - one that chronicled time and shared interests and values that never faded while memorializing Dad in a most considerate and intimate way - our friendship was reconnected after nearly four decades.

My son, Jake, had recently gotten the fly-fishing bug after going out a couple of times with a British friend in his shooting sports group. He had become proficient casting a fly rod and catching panfish and small bass by 10. At eleven I had guided him to his first rainbow in the tailrace of a river closer to home, but baseball and bird hunting had occupied his interests and time since.

Graduating college and starting a career brought golf and fly-fishing back into Jake’s sphere of interest. It being one’s considered opinion after 61 years of life that a man who has bird hunting (and a bird dog) and fly-fishing can find the solitude, happiness, and quiet mind to survive most of what life will throw at him, I was none too disappointed about the new development.

A few weeks after Richard’s thoughtful gesture, I texted him to let him know I was bringing Jake up to the mountains to fish and asked if he’d like to join us. He was busy that morning, but noted that the power generation schedule regulating the flow in the Toccoa tailrace left a couple hour window, and invited us to come by in the afternoon and fish at his place.

Until I arrived with Jake, I had not seen it. But the incredible beauty of Richard’s riverfront cabin and property, and his relationship with the rainbow and brown trout in the deep hole in the bend of the river adjacent to it, are worthy of their own separate post in these pages.

After a brief tour, we rigged up. From the grassy bank under river birches that frame the view out over the river from his cabin like a Norman Rockwell painting, Richard pointed out several flows and chutes and falls that ordinarily hold fish.

We let Jake set out on his own, watching him hit the first couple of spots. Richard complimented Jake’s nice, tight loops. I smiled and responded, “Hand eye thing. Like baseball. Wait till you see him shoot sporting clays. Teach him how to mend line, will you? You’re an expert and I suck at it.”

We eased into the river like the 60+ year-olds we are and carefully worked our way just below a couple of likely holding spots. After a few minutes, Richard came wading downstream toward Jake thirty yards below us and across the river and waved me in his direction. Meeting him about halfway, he stuck out his rod and said, “switch, throw this.”

Since we were not in the confines of the tight creek where he had tried to do the same three weeks earlier, but on the open river where there was no chance I could rap the tip on a rhododendron or oak branch, I dispensed with the fear of breaking his hand made heirloom. I took his bamboo rod and handed him my graphite one.

Richard waded down and across to give Jake some line mending help. I eased over to reach a small fall beneath a log close to where I had stashed a thermos full of peach sweet tea near the downstream edge of Richard’s property.

I pulled out twenty feet of fly line, wiggled a couple of feet of it out past the rod tip, and let the river’s current and the line’s weight pull the rest through the guides. Once all the stripped line was through the guides and on the water downstream, I lifted the rod tip until the line came taught and the tiny caddis was dancing on the surface, and with a quick movement of my arm and a sharp snap of the wrist lifted the fly into the air.

The bamboo piece of art came alive in my hand. Its slower “action,” as it is known among anglers, has a unique, alive feeling in your hand that graphite just can’t match.

That wonderful, wobbly, whippy feeling in my hand instantly transported me back in time, to where my life outdoors began as a kid. I threw a few casts for the sole purpose of remembering that feeling in my hand, recalling where I first felt it nearly 60 years earlier. And I thought of the man in the framed picture who started it all.

I waded over to the bank, set the rod down, and sat with my boots dangling in the cool, gin-clear water. I poured a cup of peach sweet tea from the thermos and lit a cigarette.

Picking up Richard’s rod again, I closed my eyes for a moment, picturing and remembering the first time I had that feeling with a piece of bamboo in my hand, not quite 4 years old, not far away.

In the summer of 1968 Dad took me for a Saturday drive in the north Georgia mountains. We hiked a short distance on a trail along one of the many (then) remote creeks he knew from his days as a counselor at a nearby camp. Late in the afternoon we ate at an old fish camp and marina called Laprade’s on a nearby lake that had originally been a construction camp for workers building the lake’s dam in the 1920s. Afterwards, dad walked into the broken-down little tackle shop and bought a “cane pole” and a small container of red wigglers.

A cane pole is a simple cut and varnished bamboo pole, usually 6-7 feet long. Monofilament fishing line of about the same length is tied to the thin end (a string will do in a pinch). A hook tied to the other end of the monofilament, a piece of lead split shot riding a foot or two above the hook, and a red and white bobber connected halfway between there and the rod tip complete the rig. No reel, you just bait the hook and swing the long rod over to the spot you want and drop it in the water. Think of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

Dad sat down on a finger dock at an empty boat slip and sat me on his lap. He pointed out the little panfish - mostly red breasted sunfish, with a few shellcrackers, and maybe bluegills - under the docks. The patience and teaching skills a man learns as a camp counselor get tested in a vastly different context when he becomes a dad.

He let me dig my tiny fingers into the dirt and touch the live worms in the cardboard container. He pulled one out and placed it on the hook, warning me not to touch the pointy metal thing from which the worm dangled, wiggling like crazy.

A group of panfish cruised through the open water in the boat slip. With both of my hands on the rod underneath one of his, dad swung the line and bobber and worm into the clear, greenish-tinted water. In a manner of moments, a chunky redbreast sunfish grabbed it. A quick snap of Dad’s wrist and the limber bamboo rod began pulsating in spasms as the hooked fish, darting and swimming in circles and trying to pull that rod out of my hand, went berserk.

I do not recall how many panfish we caught and released. But, the feel of the thing in my hands, the colorful, alive creatures tugging so mightily that but for Dad’s hand on the rod they would have pulled it me, and the awe, thrill and bug-eyed wonder I experienced as they emerged from the water, dad carefully grabbing each so as not to get stuck by a spiny, sharp dorsal fin (cautioning “don’t touch these!”), are with me to this day. Particularly the feel of that bamboo rod.

He let me touch each fish, the slime, the ridges of the scales, careful not to let me touch the spiny dorsals, prick my finger and ruin the moment. Smiling, he said, “smell your fingers!” letting me smell his own hand first for reassurance.

I held my fingers up to my nose. A bewildering new sensation, gooey like snot and smells funny! My not-quite-four-year-old mind was on sensory overload: What is this thing we’re doing? How does he know how to do this? How fun and amazing is THIS?!?!

The sun was descending toward the skyline of forested green mountains to the west, and we had a two-hour drive back to town. Setting me on the dock, Dad stood up and, scooping me up with one hand and the cane pole and what was left of the cardboard box of worms with the other, announced we had to go home. “Don’t worry, we’ll go fishing again real soon!”

I don’t actually remember it, but according to the way Dad recounted the story on more than one occasion, I burst into tears and started screaming bloody murder. “Noooooo!”

At about seven, when I could be trusted to fish alone with my dog in the suburban creek running through neighbor’s backyards, Mom received a phone call from Mrs. Shore four doors down.

Red breasted sunfish, shellcrackers, bluegills, and a few small catfish hid out in the deeper bends in the creek behind Mrs. Shore’s. “Is everything OK, Sharon? Is he getting enough to eat?” I can only imagine the confused look on Mom’s face. “He’s fine! Why do you ask?” Mrs. Shore explained, “well, honey, he just came to my back door and asked if I had any salami, and I got worried!” Mom, knowing exactly where I was with my cane pole, burst out laughing and explained I had obviously run out of bait.

I sat on the bank of the river, false-casting Richard’s rod a few more times to remember that feeling in my hands from almost 60 years ago. I closed my eyes again and thought about all the days and years that had passed. And I thought about dad, and what that day at LaPrade’s in 1968 had triggered, how a lifelong passion for the outdoors that began with a bamboo cane pole on Dad’s lap had shaped all the days of my life.

How it had shaped my relationship, not just with birds and bird dogs and fish, but with the environment, how I valued it, and my place in it.

The role it played in the people with whom I surrounded myself, and the many rewarding, lifelong friendships I have made - and am still making - as a result.

The relationship it cemented with my father, and the incredible reward from paying that forward, with my own son.

And the rewards reaped from placing far greater value on the experiential than the material, no small thing having seen the ugly, anxiety ridden consequences of the converse.

In his beautifully written 2010 book, “A Hunter’s Confession,” Canadian author David Carpenter recounts a story by Walter Linklater, an Ojibway First Nations elder, counselor and spiritual leader in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan:

Before a hunt, for example, the men would light a smudge from sweetgrass or some other plants, and they would take the smoke to their firearms to purify them before the kill. The animals were as much a part of their families as their own people so to hunt them without reverence would be unthinkable.

Totemtik. This is a Cree word that Walter gave me so that I might understand this reverence for the animals. “Totemtik means all my relations, human and other.” He does not have dominion over the animals, he is connected to them.

All my relations, human and other, lived through nearly six decades in the outdoors. That is the genesis of this Substack.

The beautiful, wild places that birds and gamefish inhabit are the canvas. Family and friends, birds and bird dogs, and fish are the oil paints. Totemtik is the Substack where the two come together, over all four seasons, covering 80 degrees latitude across two continents, over half a century.

Welcome.

“Like” this post if you, too, have outdoor passions.

Leave a comment. Share your own stories. Let’s make this a forum!

Subscribe to Totemtik for free below.

Please share this post with friends and family, especially those who love bird hunting and fly-fishing.

Lovely memories, thanks for sharing. Will follow your Substack with interest.

You speak my language…… although I’ve never met you I feel like we’re friends from the depths of your writings. This is going to be epic! This put my mind in historical movie mode, and that is greatly appreciated. Remembering the outdoor experiences introduced by my parents that started my passion for them as a kid, and continues to this day🇺🇸